|

|

King Roger Opera in Three Acts by Karol Szymanowski

Opera? It’s been some fifteen years (c.2002) since attending an opera. The last time was taking my early-teen step-daughters Nicole and Natalie to Sydney to see the double bill of Mascagni's Cavalleria Rusticana and Leoncavallo's Pagliacci. Since then I’ve been reluctant to go to the trouble or expense of going to Sydney to see a repeat of operas seen before or to take the chance of seeing a new opera in case it disappointed. So, noticing a reference in the newspaper recently to a new opera for Opera Australia would ordinarily have sparked scant interest. But this opera was titled King Roger. That caught my attention; and inevitably led to finding out as much as I could about the opera: why an opera about King Roger? Who was Karol Szymanowski, the composer mentioned in the articles? What was the inspiration behind it? Inevitably, the end result was a determination to see it. And I did. Well you might ask, “who was King Roger?” King Roger II

In keeping with the quirks and complexities of both Middle Ages and Middle Eastern history, Roger was from a Norman family. The Normans were descendants of the Norsemen, essentially pirates and raiders from Scandinavia who had settled in and had given their name to the area of Normandy in France. Roger’s father had migrated from Normandy to what we now know as Italy in search of new lands to conquer, control and tax – not an uncommon practice in those times. By the time his son, who would become King Roger II of Sicily, took control of his father’s acquired domains, they included all the Italian peninsula south of Rome, the islands of Sicily and Malta, as well as a stretch of land along the North African coast encompassing parts of today’s Tunisia and Libya. This was Roger’s kingdom when he became King of Sicily in 1130, although he had control over the domains from 1112. The capital of his kingdom was Palermo on the island of Sicily. He reigned until 1154. But why an opera about King Roger? What was so famous or interesting about him? Roger was a stand-out monarch who was accepting and accommodating of all cultures, religions and ethnicities. Even more than that, he actively and inspirationally utilised the talents, philosophies, laws, literature, architecture etc. of the multicultural lands he inherited. Palermo became a centre of government and learning that welcomed and benefited from a wide diversity of peoples of all backgrounds and religions. Roger himself was fluent in both Latin and Arabic; and both languages were widely used in government business.

Even today, some nine hundred years later, Sicily offers the tourist an insight into all aspects of its history, with Greco-Roman ruins, mosques, cathedrals, castles and palaces; with perhaps the pièce de résistance, being Roger II’s Cappella Palatina (Palace Chapel) at Palermo: “the most wonderful of Roger's churches, with Norman doors, Saracenic arches, Byzantine dome, and roof adorned with Arabic scripts [ - ] perhaps the most striking product of the brilliant and mixed civilization over which [Roger II] ruled." (from 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica). Karol Szymanowski

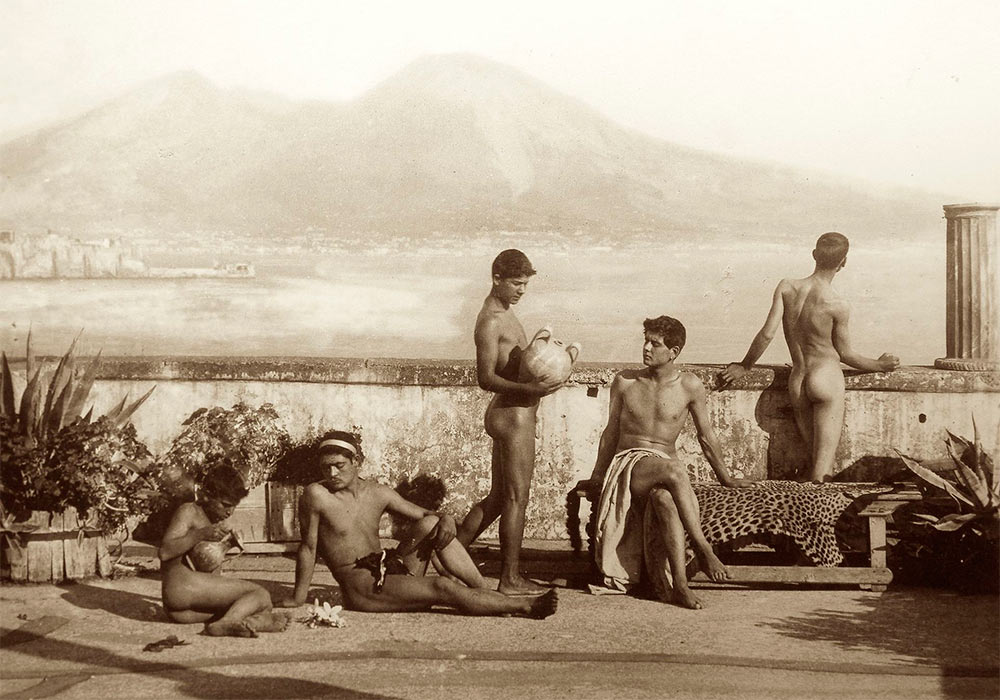

Karol Szymanowski was a Polish composer and pianist whose life traversed the 19th and 20th centuries: 1882 to 1937. He was landed gentry stock with estates in the Ukrainian part of the then Russian Empire. Inevitably, therefore, he was deeply affected both physically and psychologically by the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 during which the family estates were seized and his beloved piano destroyed. Perhaps far more of an effect on Szymanowski as a person and as a composer were his early struggle with is sexual identity and his self-imposed obligation to showcase Polish folk history. Initially he suppressed his homosexuality behind the façade of Polish upper class conservatism; and much of his early music reflected Polish themes. However, his travels (this was before the 1917 Russian Revolution), in particular to North Africa and Sicily, opened to him two lasting experiences. North Africa imbued him with a fascination for Arabic culture and sounds. Sicily, whose sensuous youth, already captured extensively by the German photographer Wilhelm von Gloeden, allowed him to be more openly accepting of his homosexuality; although not making it any less tormenting for him in his Polish society. Both of these aspects had fundamental impacts on his musical – and in one case, literary – compositions. By the time he began his composition of King Roger in 1918, he had already written musical works that were clearly redolent of Arabic themes; and he had tried his hand at a novel, Ephebos, exploring aspects of male beauty and love. Apart from any erotic souvenirs he might have mentally cherished from his time in Sicily, he was deeply affected by his encountering the life and reign of King Roger II and Roger’s legacies both in terms of his acceptance and employment of people of all races and religions; and his architectural monuments incorporating elements of Sicily’s almost unique mixture of history. From all of this emerged his inspiration for the opera King Roger. Back to the Opera

Many descriptions of the opera, including those contained in the Opera Australia program, allude to the elements that inspired Szymanowski: the church interior in Act I modelled on the Cappella Palatina, “with its golden mosaics, Roman ceiling, choirs in full voice, and priests in brocaded robes swinging incensories” which are described as establishing “the scale and power of the religious and political orthodoxy the shepherd will undermine in the course of the opera;” and the ruins of an ancient amphitheatre in Act III where the shepherd appears as Dionysus (the Greek god of wine inter alia, but whose cults became more associated with over indulgence and erotica). Such trappings, if that’s not irreverent to describe them as such, would have, at least, retained more evidently the context that drove Szymanowski to write the opera. There wasn’t much evidence of these trappings in the Opera Australia production; and their absence, I thought, detracted somewhat from Szymanowski’s vision of his work. The Opera Australia version – or, perhaps more precisely, the Kasper Holten version – had its own context and setting characterised by a giant head dominating the stage in Act I symbolising the intellectualism of Roger’s approach to life. The head turned for Act II to provide a view inside the head of a multi-storey dwelling in which most of Roger’s inner agony takes place. While that works effectively for the fundamental theme and message of the opera, it pretty much erases any traces of King Roger II or his times, except for two characters in Act I dressed in Christian Orthodox robes but looking somewhat anachronistic being surrounded by the “choir” in 1950s style dress. Roger in the opera could have been anyone at any time. The opera could have been renamed after any contemporary public figure.

A particularly forceful element of the setting was the rendition of what Kobbé’s Complete Opera describes in Act III: “the shepherd has by now turned into the Greek god Dionysus and the members of his train into bacchants and maenads; and they whirl into a mad dance…” Don’t be dismayed, I had to Google them too: essentially intoxicated, frenzied revellers; the maenads being female followers of Dionysus. In the Australia Opera version (more in keeping with Szymanowski’s demons) a troupe of male bacchants or male-equivalent of maenads engaged in erotic and sensual intertwining, like snakes in an Indiana Jones scene, at pertinent parts of Acts II and III, compellingly capturing what Roger was fighting against as he tried desperately to cling to his intellectual and spiritual values. Although it was basically a fascination for King Roger II that drove me to see the opera – as it was for Szymanowski, according to one commentator, to create the opera (or, more accurately, to choose the context and setting for the opera), I went to it already knowing something of what it was about in reality. So there were no surprises other than my thorough enjoyment of the experience. 4 February 2017 |

You’ve probably never heard of him; and nor had I until a few months ago. It was one of those fortuitous coincidences. I recently indulged in a series of lectures about “Turning Points in Middle Eastern History,” all of which were fascinatingly informative. One was devoted to King Roger II of Sicily, whose reign was considered one such turning point.

You’ve probably never heard of him; and nor had I until a few months ago. It was one of those fortuitous coincidences. I recently indulged in a series of lectures about “Turning Points in Middle Eastern History,” all of which were fascinatingly informative. One was devoted to King Roger II of Sicily, whose reign was considered one such turning point.  What Roger established and cultivated was, in effect, a government and society built on and utilising the rich history of Sicily. From the initial times of documented history, there were, first of all, Greek city-states, the most famous of which was probably Syracuse. Then occupation by the Roman Empire, followed by the Byzantine Empire, the successor of the Eastern Roman Empire. From around the eighth century, with the spread of the Arab/Islamic rule across North Africa, it was subject to periodic raiding until eventually taken over in the ninth century by the Aghlabid emirs who controlled parts of North Africa; and eventually in 909 came under the control of the Fatimid Caliphate. it remained under Arab/Islamic rule, although retaining a largely Christian population, until the Norman invasion by Roger’s father in 1061. Not relevant to this story but interesting to note that this was just five years before another Norman, a kinsman of Roger’s father, William the Conqueror, invaded England in 1066.

What Roger established and cultivated was, in effect, a government and society built on and utilising the rich history of Sicily. From the initial times of documented history, there were, first of all, Greek city-states, the most famous of which was probably Syracuse. Then occupation by the Roman Empire, followed by the Byzantine Empire, the successor of the Eastern Roman Empire. From around the eighth century, with the spread of the Arab/Islamic rule across North Africa, it was subject to periodic raiding until eventually taken over in the ninth century by the Aghlabid emirs who controlled parts of North Africa; and eventually in 909 came under the control of the Fatimid Caliphate. it remained under Arab/Islamic rule, although retaining a largely Christian population, until the Norman invasion by Roger’s father in 1061. Not relevant to this story but interesting to note that this was just five years before another Norman, a kinsman of Roger’s father, William the Conqueror, invaded England in 1066. Before getting to the opera, however, it’s essential to look into the life and times of Karol Szymanowski, the composer. That’s because this opera, possibly much more than any other opera, is a manifestation of the person and inner conflicts of Szymanowski himself – an attribute that makes the opera all the more beguiling and intriguing.

Before getting to the opera, however, it’s essential to look into the life and times of Karol Szymanowski, the composer. That’s because this opera, possibly much more than any other opera, is a manifestation of the person and inner conflicts of Szymanowski himself – an attribute that makes the opera all the more beguiling and intriguing.

On a much more positive note, the drama, music, singing and staging (notwithstanding comments above) were hypnotic. I can’t say I fully appreciated the roles of Polish folk music and Arabic melodies alluded to by analysts; but then I haven’t been endowered with many music appreciation talents. What was appealing and attention-grabbing was the combination of dramatic acting and mesmerising music and singing. Appreciating that at the core of all this was the composer almost unabashedly offering the audience an insight into his own very personal demons rendered a unique opera experience.

On a much more positive note, the drama, music, singing and staging (notwithstanding comments above) were hypnotic. I can’t say I fully appreciated the roles of Polish folk music and Arabic melodies alluded to by analysts; but then I haven’t been endowered with many music appreciation talents. What was appealing and attention-grabbing was the combination of dramatic acting and mesmerising music and singing. Appreciating that at the core of all this was the composer almost unabashedly offering the audience an insight into his own very personal demons rendered a unique opera experience.